Could the popular gene-editing technique CRISPR-Cas9 create the basis of a DNA-based data storage device? The CRISPR adaptive immune system found in many bacteria memorizes viruses by storing snippets of the viral DNA. This virus DNA memorization happens rarely. But, it turns out that there’s a single mutation in these bacteria that lets them store genetic memories of viruses 100 times more often than they would naturally. This naturally ocurring mutation in the Cas9 gene enables the Cas9 enzyme to more readily acquire snippets of a virus’s DNA that would enable it to protect itself in future meetings with that virus. Microbes replicated with this particular mutation have enabled research scientists working in UC Berkeley’s Laboratory of Bacteriology to generate much more data about various aspects of CRISPR.

Could the popular gene-editing technique CRISPR-Cas9 create the basis of a DNA-based data storage device? The CRISPR adaptive immune system found in many bacteria memorizes viruses by storing snippets of the viral DNA. This virus DNA memorization happens rarely. But, it turns out that there’s a single mutation in these bacteria that lets them store genetic memories of viruses 100 times more often than they would naturally. This naturally ocurring mutation in the Cas9 gene enables the Cas9 enzyme to more readily acquire snippets of a virus’s DNA that would enable it to protect itself in future meetings with that virus. Microbes replicated with this particular mutation have enabled research scientists working in UC Berkeley’s Laboratory of Bacteriology to generate much more data about various aspects of CRISPR.

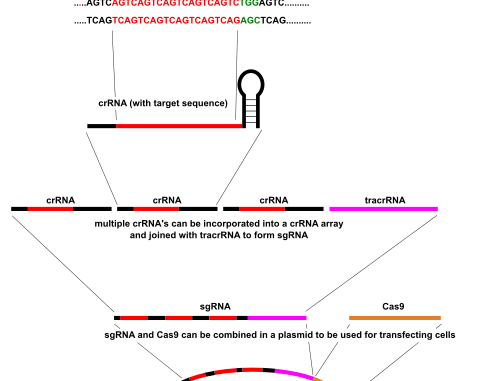

The Cas9 mutation could make it possible to develop a DNA-based recording system that could be adapted to acquire information about activity of neurons, cellular responses to environmental stimuli, or the trajectory of metastasizing cancer cells. There’s one caveat though — Cas9 is used in the CRISPR process to destroy an invading virus. Sometimes the naturally occurring CRISPR system instead of defending its cells from a virus, misfires by acquiring DNA snippets from its host rather than from the virus. In that case, the cell simply kills itself. While researchers face many hurdles, this development has introduced a new laboratory tool that can potentially make a CRISPR-based recording system a more realistic objective.